To build the world in the I, to behold the I in the world, is breathing of the soul.

To sense the universal all in feeling of one's inner self is wisdom's pulse.

To trace the paths of the Spirit in one's own aims of life is inner speech of Truth.

So let the Soul's breath penetrate into the pulse of wisdom

Calling forth from inmost depths the speech of Truth

Through all the rhythms of the years of life.

Today I'd like to bring a little bit of a closure to our work on spiritual physiology. The work that Rudolf Steiner did in spiritual physiology is immense, and if you are interested in undertaking it, it can consume a lot of study time in your life. But every minute spent studying it is well worth the effort, because it has a great deal to do with what we could call turning the soul, a higher level of spiritual work. Today I'm going to talk about turning the heart, which is the basis for turning the soul. The great mystery of the universal transcendent experience called dying to self, centers on a biological fact in embryology having to do with the formation of the heart.

Embryologically the heart begins in the first week, outside the organism as four vortexial streams in the amniotic fluid of the fetus, and those streams are all going towards a common center. But somewhere in the very beginning, in the first two weeks or so, these vortexial heart streams begin to move into the embryo; these four streams in the amniotic fluid around the embryonic disc are sometimes called the four rivers, like in the Bible, the four rivers in Paradise. The vortex comes in from the top through an opening where the mouth will form. Down below and coming up within the actual body of the embryo there are two veins which come into the gut area from the yolk sac which is outside of the embryo but attached to it at the umbilical cord. These veins are called the yolk veins. At this early date the yolk sac is shrinking to be replaced by the placenta, but the yolk veins penetrate the embryo and serve as the formative source of the liver, which emerges as a bud of the yolk veins in the third week. The liver is attached to the body wall by a ligament. Further up towards the head from the liver, another bud of the yolk veins is forming into the lungs. In between the lungs near to the head and the liver buds in the gut area, the yolk veins form twin tubes stretching from the liver to the lungs. These two parallel tubes are surrounded by what is known as cardiac jelly, a formation of the creative layer of the mesoderm. The vortex coming down from the head meets the two tubes coming up from below and the two tubes from the yolk veins begin to wrap around each other. The ligament which anchors the liver serves as a fulcrum for the spinning of the two tubes as the bottom of the tubes moves up towards the head and the top of the tubes moves down towards the tail end of the embryo. In the spinning the two tubes get folded into four chambers and the original two-chambered heart now has magically become a complex heart capable of an advanced circulation. There are two upper chambers (the atria) and two lower chambers (the ventricles).

Atrium is Latin for the little porch that you go into before you go into a house or into the temple. That's the atrium. It's the hallway. A little porch. So that is the place in the heart where the blood comes into the house, in the atrium. And the ventricle has in it the word vent. So the ventricle is where the blood goes out of the vent. So you have two atria and two ventricles. But how they're arranged is very ingenious.

This is fundamentally the heart organization for the higher animals. All the invertebrates and some of the vertebrates (fish and whatever) until you get up into the reptiles have simple multiple chambered hearts composed of series of tubes. In the higher animals and the human being the chambers are arranged to be reciprocating and are not simply a series of tubes. The reptiles have features which reveal a transitional pattern between the lower heart forms and the higher heart forms. In a crocodile heart there are little fingers between one ventricle and the other ventricle, which upon opening allow the old blood to mix with the new blood. When the crocodile heart fingers are open the flow of blood to the lungs is reduced, and the blood flow from the right ventricle, which is receiving blood from the liver, is shunted off into the left ventricle for circulation through the body. In this mode the heart is, in effect, a single tube.

This is the arrangement that you have in the higher embryo before birth. The lung circulation is not needed because the placenta brings oxygenated blood from the mother. In the crocodile this capacity is useful when the animal is submerged for a long period of time. A crocodile hunts by grabbing its prey and heading for the bottom. It stays down long enough to drown the prey and bury it in a lair on the bottom. While submerged the fingers of the heart are open and the flow runs from liver to right ventricle to left ventricle just as in a human fetus. On land the crocodile closes the fingers between the ventricles and the blood then moves through the lungs. This is similar to the condition in the embryo that begins to happen at term when the blood needs to flow into the lungs. At birth a flap of skin closes a hole between the ventricles as the pressure on the left ventricle gets greater because of the increased flow from the lungs into the left side of the heart. The crocodile does this depending on outer conditions of temperature and water pressure and whether it gets enough oxygen, all of the variables, which need to be dealt with when a higher animal leaves its watery life in the womb and is born onto dry land. The crocodiles develop a special organ in their heart as a prophecy of what is to come.

So we see in the two-chambered heart of the early mammalian embryo a recapitulation of the plan of the heart of all of the lower animals, and then in the higher animal that two-chambered heart around the third or fourth week goes through an inversion. We could say there's a change of heart. There's already been a change of heart from the paradisiacal heart, the vortex in the amniotic fluid, into the heart of all the lower animals. Now there's a change of heart into the heart of the higher animals. This is in the third week. And in order for that to happen, there needs to be a reversal of the two-chambered heart that fundamentally has blood just flowing through it and mingling. In most lower animals the red blood and the blue blood mingles and circulates throughout the body. There is often little differentiation that happens in the flow patterns in those two channels.

In the very early embryo of a higher animal, the simple two-chambered heart is really only formed into two chambers by the most tenuous of separations. In this heart, the septum is just a mesodermal jelly. It's not really a membrane until much later. It's just a jelly. So the blood goes in and out in the circulation of the vortex and the blood beats on the mesodermal jelly. In this jelly walls form, sort of like sand in a current of water. It septum forms in the currents of the vortex, like a sand bar made of pericardial jelly. So the septum of the heart, the division, just forms as a mesodermal jelly that gets hit by the impact of the currents shaping it, and eventually those impulses cause bulges to happen. Then in the third week a dramatic gesture grips the entire embryo. The potential being bends its head from the cervical vertebrae at the level of the future pineal gland and the whole upper spinal development is altered. Suddenly this whole apparatus of nerve and blood turns upside down and parts of it actually gets tied in a knot.

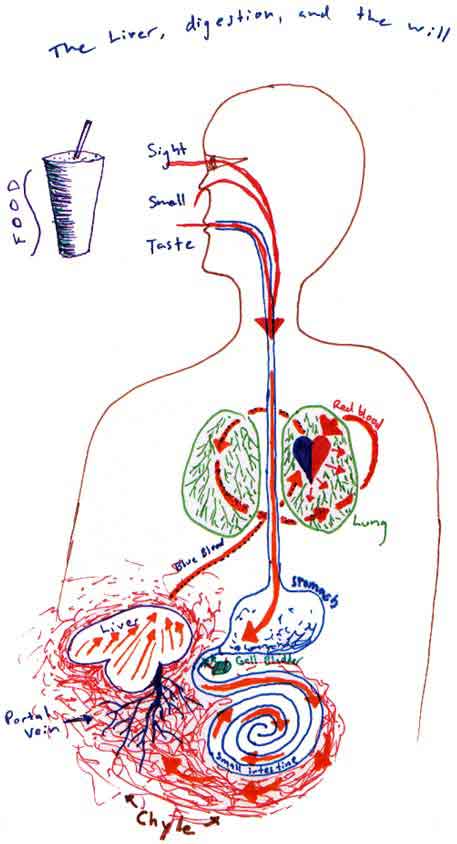

When that happens, you get something that looks like this. (See diagram above.) This blue one is the vein, the blue blood moves through the vein. The big vein coming into the top of the heart comes up from the liver, and then goes into the heart into the venous or right atrium. In a fully developed heart, the blue blood goes into the right atrium from the liver, then goes down into the right ventricle and from there it moves up into the lungs where it becomes red blood. The red blood then comes out of the lungs and down into the left atrium where it descends into the right ventricle and then on into the aorta which emerges in a whole ring of arteries at the top of the heart which resembles a crown.

And when one chamber at the top is going flub and filling with blood, the other chamber at the bottom is going dub and emptying. It goes flub-dub, flub-dub, flub-dub. When one fills, the one across from it empties, and then the other one fills, the other one empties. There is an action that goes crosswise across the heart. From below, and in at the top, from the top down to the bottom and then up. Flub-dub.

So as an organ, the "becoming" of the heart is a series of reversals. That's its evolutionary path. Whereas the kidneys had to fall and come back up again, and the liver gets pushed up from below only to run into the ceiling of the diaphragm, and the lung gets pushed up from below and then opened up from above -- the heart keeps going OK I can do that, OK I can do that also. And each time it replicates a motif from another life organ, it gets more complex with each inversion. That's a picture which points out the best way in which to educate the heart to see. But we'll go there a little later.